As electronic music production has gotten more accessible over the past decade and a half, it has pushed producers to get creative in exciting ways. We have seen pieces of hardware used to create electronic music we never thought possible and this album from Berlin-based composer and musician Hainbach is up there with the most unique. He worked with aged high-end research equipment that was no longer in use, taken from nuclear research labs, particle accelerators and grandfathers' sheds. These were stacked together (as you will see below) in what he called the Landfill Totems, which is the title for the album.

The sounds that come from these totems are shape shifting, sometimes bizarre and always riveting. There are moments that are alien-like where the album heads well beyond the human conscious with “Segen” and then pulls you back with more haunting drums and even Morse code. You can feel the old, machinery creaking to life in a way it had never been used before, giving it new purpose. Electronic music is supposed to be on the cutting edge and with particle physics and nuclear research, those should, and do pair exceptionally well with this project.

To get a better idea of how this project was created, we asked Hainbach to show us how it was made. He breaks down a few of the different pieces of gear used to create this project. This won’t look like your traditional music studio, so expect the unexpected with the Landfill Totems. He starts with the overall album and then dives into some of the individual pieces used on the album.

Pick up your copy of Landfill Totems here and listen as you read.

Landfill Totems: This album came first from necessity – I ran out of space in my studio because of the all the huge chunks of obsolete test equipment I kept buying and prodding to see if they would "music." When I got offered a residency and PNDT Art my first thought was "great, I can keep acquiring stuff because I got a space to store it now." When I moved a van full of equipment there I realized to my dismay that in the big white room everything looked tiny. So instead of copying the wall of test equipment in my studio I decided to stack the instruments differently, and within half an hour the first statue came into being. It looked curiously human, yet multifaceted as all the dials form smiles, curious frowns and totem-like faces. Within four hours I had built two more and started patching them together. The name "Landfill Totems" and the music that I created felt like it came as much from them as me.

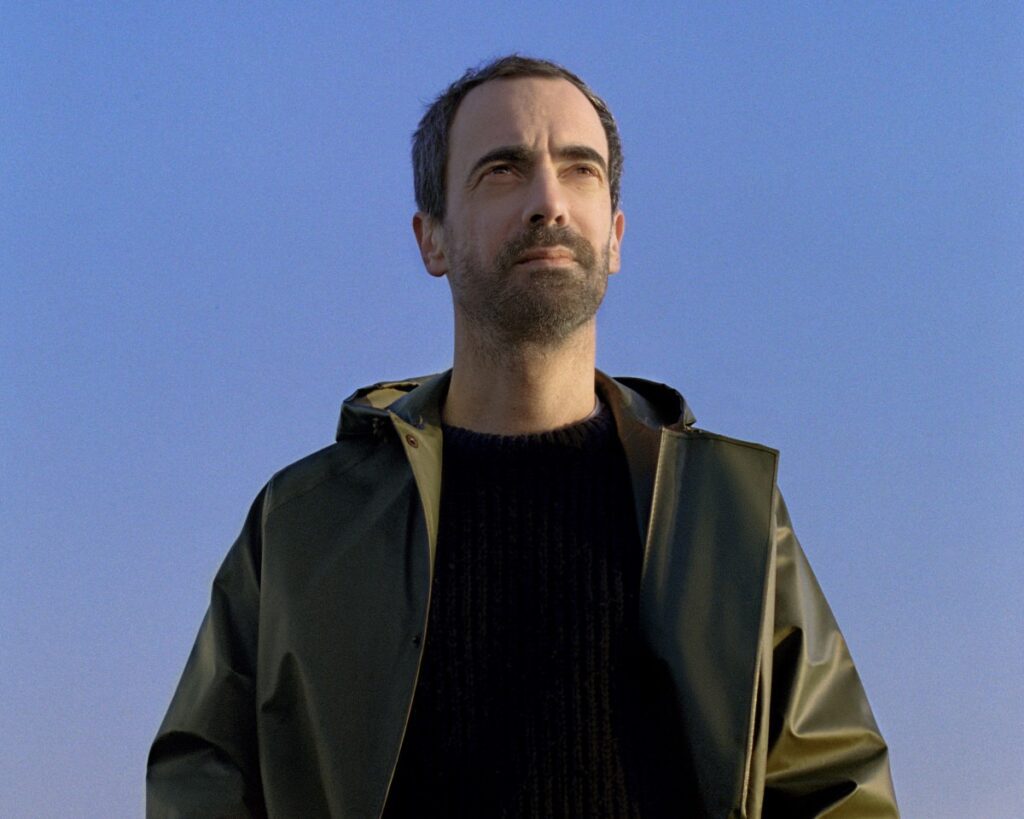

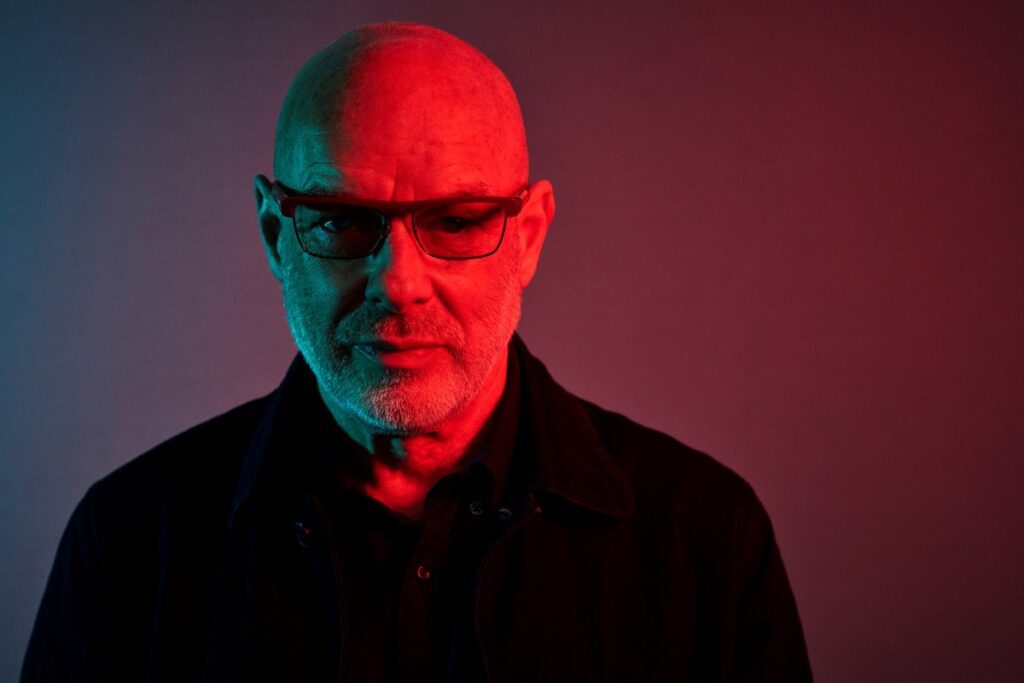

In this picture, you see me with two of my Landfill Totems at Patch Point in Berlin. This is an early picture, before the spider web of cables connects everything. Note that they are not stabilized in any way, so the audience (and me) are always rather weary of being crushed by them. I like that sense of threat — it adds urgency.

Hainbach & his Landfill Totems

Hainbach

1. Brüel & Kjaer 1615 Bandpass Filter:

The Brüel & Kjaer 1615 Bandpass Filter was essential for the recording of the album – when you send it short impulses it will produce anything from soft bass drums, woodblocks to underwater sounds. In the associated library instrument, the patch "Water" gives you that sound in your computer. I have to be careful not to overuse it myself.

Brüel & Kjaer 1615 Bandpass Filter

Hainbach

2. FG504

Tektronix made modulars before Bob Moog. They pioneered assembling your own oscilloscope or test setup in the 1950s. This wonderful FG504 function generator is from the later TM500 format and can be described as a complex oscillator – it does FM beautifully. It is the core voice on the track "Funktionsverlust" and instead of its usual straight drone it does a little samba pattern, which surprised me. I learned the reason right after recording as magic smoke poured out of the unit. It's funky dance was also it's swan song. Just one of many units that died during the making of this album, sadly.

FG504

Hainbach

3. Schwebungssummer:

These are two rare and utterly fantastic German units – the Schwebungssummer produces deep sines and works as a very good vacuum tube amplifier for external signals. It sounds very unlike a synth, but not technical at all. It is on "beauty" duty all over the record, but also to transform harsh clicks into something listenable, as with high gain you get weird resonances. The Signalspeicher SS01 underneath is the world's shortest looper – at highest speed it does 19ms of recording on a tiny tape loop. Wonderful for microsound application, and since this was modded for vari-speed it is very effective for slow down / speed up effects as well as "floppy tape" rhythms.

Schwebungssummer

Hainbach

4. Specular Tempus

Electronic music would be nothing without a surreal body of effects, and the GFI Specular Tempus is all over the record. It was the sole reverb, though it is also a Harmonizer at the same time. I love this so much because the "vocal" program makes everything sing.

Specular Tempus

Hainbach

5. PG303

If you think of some of the earliest electronic rhythms ever made, you can't not mention morse code. The Data Products PG303 is designed to send these patterns for telephone/radio testing, and is one of the strangest rhythm machines I know. It is probably half broken and gave me a nasty shock or two as I wired the power wrong, but it is always inspiring. On the album, this drives most of the rhythm, and in the library you can hear it also at higher Baud rates oscillating.

PG303

Hainbach

6. Sony D100 Recorder

Since I recorded the whole record on location at Patch Point Berlin, I brought my trusted Sony D100 recorder. The first time I heard a show of mine recorded with one of these I knew there was something special to this unit. I don't know what the engineers at Sony did, but I love every recording I make with it. The album was recorded at 96kHz and 24bit, and I am indebted to Nathan Moody at Obsidian Sound for making what I recorded and mixed headphones translate well.

Sony D100 Recorder

Hainbach