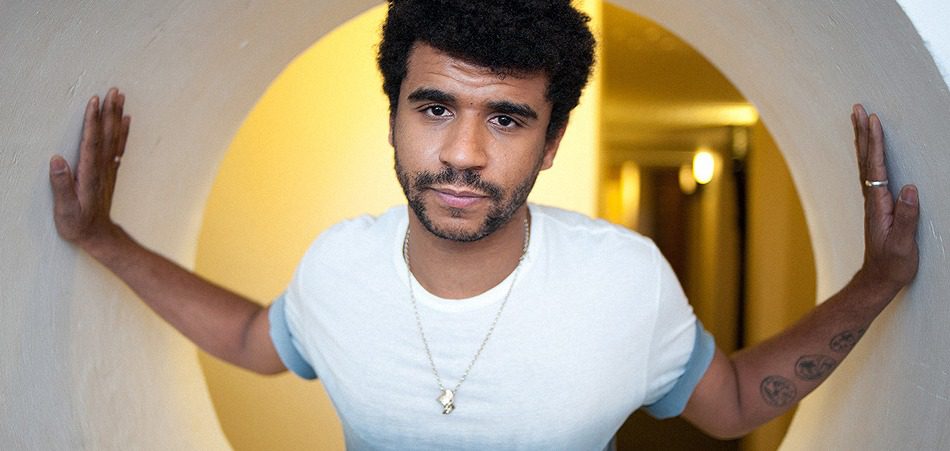

Following his introspective, definitive debut EP Butterfly Boy, Dublin-born rapper Malaki is slowly releasing singles from Cocoon, his follow up project. For the global premiere of “Cavalier”, Cocoon’s third single, I sat down with Malaki (real name Hugh Mulligan) and his longtime collaborator/production partner Matthew Harris to chat about the intricacies of the song.

“Cavalier” opens on a grim scene: a bar fight over a woman. You’d almost roll your eyes, if it weren’t for the inclusion of Malaki’s inner monologue. “Cavalier” is Malaki flexing his rap muscles. The young hip-hop artist is experimenting with the kind of braggadocio that rappers cultivate in their personas, but by using a narrative structure rather than rapping overtly about a personal experience, the Dubliner is actually sticking his tongue firmly in his cheek to critique male arrogance. And I’m not so sure he knows just how thoroughly he’s done it.

As we talk, it becomes clear that however overt the messaging in the story is, there’s also a swirling of fate about this track – its resulting subliminal messaging was being engineered hundreds of years ago, and in some ways, Mulligan, Harris and their collaborators are merely along for the ride.

Meticulously crafted from Mulligan’s initial verse and a sampled backing track that Harris showed him as a fluke, “Cavalier” is rich, both sonically and in content. Bar fight narrative gives way to a laidback, breezy vocal from Lucy McWilliams, who almost acts as a benevolent mitigating factor to the conflict. “Lucy’s vocal is the peacekeeper between myself and the guy in the story,” Mulligan explains. The song is unequivocally about toxic masculinity, which is a subject Mulligan explores in every facet of his work. “There’s a lot of subtlety in Hugh’s lyrics,” says Harris, “which point toward a dissatisfaction with who the character is, and a disconnect between his outward persona and who he is underneath it. It touches on a lot of the themes we looked at in Butterfly Boy.”

Mulligan is quick to add that he’s still a work in progress: “It’s such a slow process of adapting what masculinity is to me…When I was younger, emotions weren’t really something you showed.” He spent much of his youth hiding his tears, and is still learning to embrace them. “When I was younger, if I saw my mother crying, I’d think ‘who am I gonna cry to now?’ A good cry is something people should take on. Like a coffee in the morning,” he chuckles.

Harris’ production is distinctly ecclesiastical. The opening notes of “Cavalier” sound like a choir of monks, before it eases into a beat. “I never really use samples in my production,” Harris admits, “but I really liked the sound of it. I wasn’t trying to make a song, I was just experimenting.” In Mulligan’s verse, he raps about religion, heaven, hip-hop and politics. Later on in Jeorge II’s verse, which was written to build on already-present themes, he drops the name Machiavelli – no doubt a reference to Tupac (who called himself Makaveli in later years), but it would be a mistake to ignore that Machiavelli was also the foremost Roman politics scholar of the Italian renaissance. Jeorge II is also a Dubliner, who here delivers his verse with near surgical precision – it’s a nice juxtaposition to Mulligan’s passionate, spitfire delivery.

The two young musicians outsourced five artists to create the cover art for Cocoon’s singles, based on the completed tracks. Designed by Yosef Phelan, the artwork for “Cavalier” is a modern, street art take on a sculpture from an Italian Neoclassical artist named Antonio Canova. Called “Perseus Triumphant,” it depicts the severed head of Medusa, after she has been slain by the mythological Greek hero. “We don’t give the artists much direction,” Mulligan tells me. “We let them listen to the song and create what they feel. I was so focused on that storyline itself – the animosity between the two people, that I completely forgot when I was talking to the girl, I was referencing religion. Yosef hopped onto it, and mirrored it in his art.”

There are few things I can think of that scream male arrogance more loudly than bar fights, the Roman Catholic Church, and the demonizing of Medusa in popular culture. Coincidentally, the version of Medusa’s myth that first popularized her narrative as a rape victim was penned in a work called Metamorphoses, by an Italian poet named Ovid, who predates Dante Alighieri.

Metamorphoses, butterflies, cocoons…it’s the kind of artistic anomaly that leaves you ravenous for more. You can sink your teeth into “Cavalier”, but the true delight is in knowing that this is merely the first taste of many. One thing is for certain: peeling back the layers of “Cavalier” has given me hard evidence to support my claim that we’ve only uncovered the tip of the iceberg where Malaki is concerned. He’s just getting warmed up, and already he packs a serious lyrical punch.

When the boys hang up, I’m left wondering whether they’re entirely aware of the creative gift they seem to have nonchalantly tossed into the ether of the world. I’m never one to perpetuate the myth that art just happens, that it’s born overnight and doesn’t take planning and work, but sometimes it’s impossible to ignore that you’ve struck magic. This is one of those times.

Connect with Malaki: Spotify | Instagram | Twitter

Connect with Matthew Harris: Spotify | Instagram